The Truth About USB-C Adapters: Missing Pins, Slow Speeds, and Cut Corners

Why Some USB-C Adapters Slow Down Speeds Even When They Look Like USB 3.x — and How Hidden Design Shortcuts Cause USB 2.0 Fallback

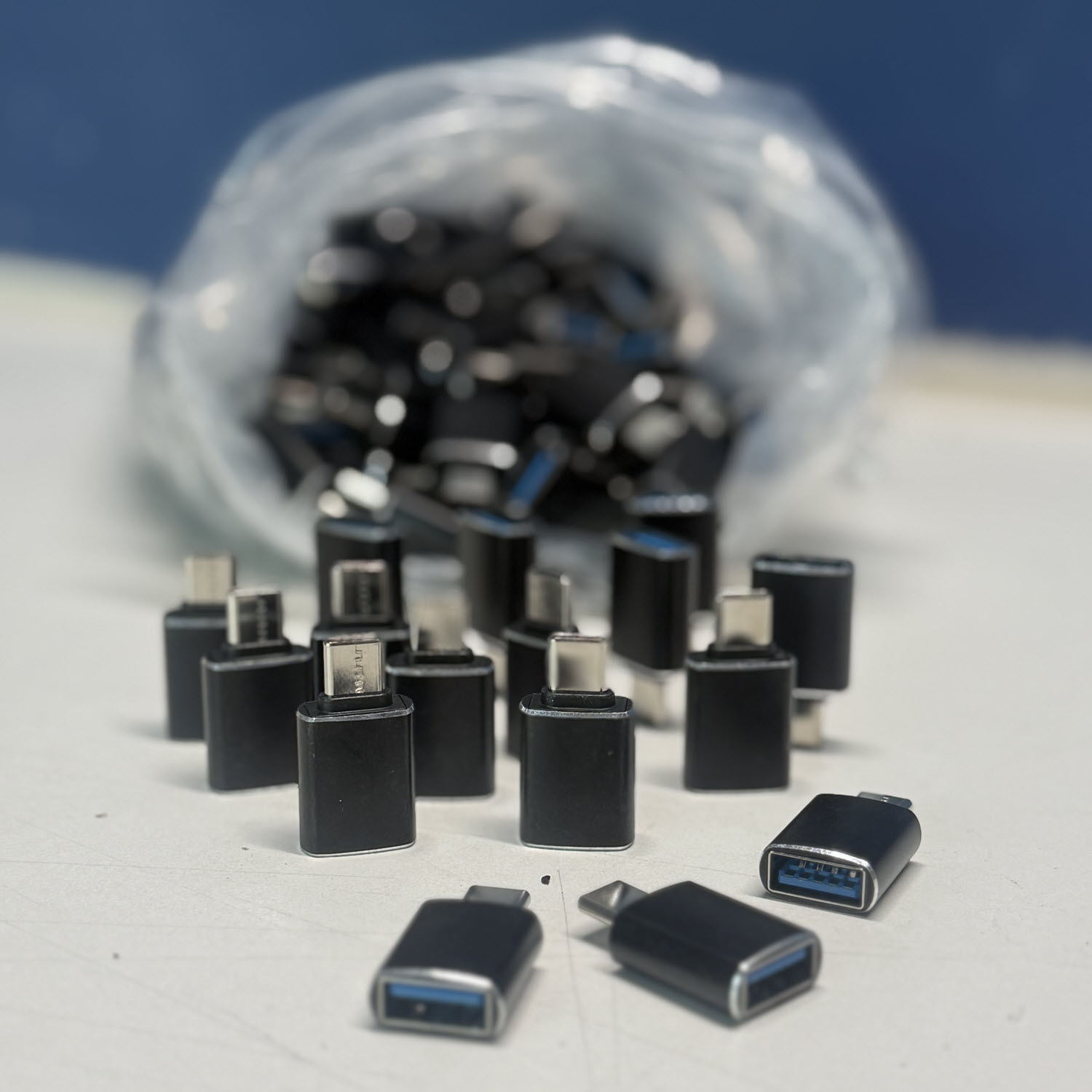

The short answer is that these adapters can slow down data transfer speeds, but not always. The adapter in the photo is a USB-A to USB-C adapter, where the blue insert on the USB-A side indicates USB 3.x capability. Whether it slows data rates depends on several factors. The first factor is what the adapter itself is rated for. If the adapter was designed for USB 3.0 or USB 3.1 Gen 1 at 5Gbps, or USB 3.1 Gen 2 at 10Gbps, it will not bottleneck performance as long as everything else in the chain supports those same speeds. However, many inexpensive adapters are internally only USB 2.0 at 480Mbps even though they appear externally as USB-C adapters, and those will slow transfers significantly.

The second factor is the capability of the device the adapter is being plugged into. Many phones, laptops, and tablets—especially budget models—only support USB 2.0 speeds over USB-C, and if that is the case, speeds will be slow no matter how capable the adapter may be. The third factor involves the speed rating of the flash drive or storage device being connected. If the drive supports only USB 2.0, it will be slow regardless of the adapter.

The adapter shown in the image in this article appears to be a typical USB-A-female to USB-C-male OTG adapter. Adapters of this type often perform poorly because many are constructed internally as USB 2.0 devices even though the USB-A port contains a blue plastic insert that suggests USB 3.0 support. Many of these adapters leave the SuperSpeed wiring disconnected, which forces the entire connection to fall back to USB 2.0 mode. These designs often have limited power delivery capability, further reducing performance when used with external SSDs.

There is a simple method for determining whether an adapter is causing a bottleneck. If a fast USB 3.0 flash drive or an external SSD is connected and only 35 to 40 MB/s is observed, then the adapter is limiting the speed to USB 2.0. If speeds above 300 MB/s are observed, then the adapter is functioning at USB 3.0 speeds. The brand or model of the adapter can also be used to verify its true capability.

Some adapters are simply pin-to-pin connectors while others incorporate logic or integrated circuitry depending on their purpose. USB-A to USB-C passive adapters, including the type shown in the article, usually contain no controller, perform no signal conversion, and include no logic chips at all. They simply passively map the SuperSpeed and power pins from the USB-C connector to the USB-A connector. Under ideal manufacturing conditions, such an adapter would support full USB 3.0 speeds without issue.

However, many inexpensive manufacturers do not connect everything correctly. Many leave the SuperSpeed differential pairs unconnected. Others wire only VBUS, GND, D+, and D?, which are the USB 2.0 pins. Some fail to handle the CC (Configuration Channel) resistor requirements properly. When any of these shortcuts occur, the device on the USB-C side will fall back to USB 2.0 only, regardless of how the adapter looks. Even though these adapters are technically passive devices, poor wiring results in slow performance.

Other types of adapters include logic or integrated chips. Any adapter that performs an actual conversion requires such chips. A USB-A to USB-C adapter that supports USB Power Delivery must include a power-negotiation IC. A USB-C to HDMI or DisplayPort adapter requires an alt-mode or display-conversion IC. USB-C hubs and OTG hubs contain USB hub controllers, PD controllers, and switching ICs. A USB-C to USB-A adapter designed to support host mode on smartphones must include the proper CC resistors so that the phone recognizes the adapter correctly.

The specific type of adapter shown in the article typically contains no main data-processing IC. These adapters normally include only a CC pull-down resistor and a passive arrangement of wires. However, low-cost models often omit the SuperSpeed pairs entirely or fail to follow the USB-C specification, which is why they frequently cause slow data transfer speeds.

The essential conclusion is that simple USB-A to USB-C adapters usually do not contain logic chips, but they still depend on proper pin mapping and correct CC resistor configuration. Inexpensive versions that cut corners frequently cause USB 2.0 fallback, inconsistent device detection, slow transfer rates, and occasional connection drops.

Many people wonder why a manufacturer would produce an adapter without connecting all the pins, since the copper and materials required are inexpensive. The reason has little to do with material cost and everything to do with manufacturing complexity and risk. USB-C SuperSpeed wiring requires extremely precise tolerances. The USB 3.0 SuperSpeed differential pairs require 90-ohm impedance matching, precise twisting, length-matching, shielding, and careful routing to maintain signal integrity at 5 to 10Gbps. Low-cost factories cannot reliably maintain these requirements.

If they attempt to wire the SuperSpeed pairs but do it poorly, the adapters will fail at high speed, exhibit random disconnects, and fail compliance testing. To avoid high failure rates, these factories simply omit the SuperSpeed lines. By doing so, they ensure that the adapter always falls back to USB 2.0, which is far more tolerant of sloppy wiring and therefore more reliable at low cost.

USB-C specification compliance also requires proper CC logic, correct routing of all transmit and receive pairs, proper grounding and shielding, and sometimes E-Marker support for high-speed or high-power ratings. These requirements increase the time required for quality assurance, raise testing complexity, lead to higher rejection rates, and increase the overall bill of materials. Low-cost manufacturers avoid these burdens by internally downgrading the adapter to USB 2.0 only.

The main cost pressure is not the copper itself but the risk of product failure. If even 5 to 10 percent of high-speed adapters fail SuperSpeed compliance testing, the factory loses money. Producing a USB 2.0-only adapter disguised as a USB 3.0 adapter dramatically reduces failure rates and helps factories avoid returns or complaints. Because consumers often assume slow speeds are caused by either the flash drive or their computer, low-quality adapters are rarely blamed, and thus marketing does not punish manufacturers for these shortcuts.

Finally, USB-C to USB-A adapters are frequently used with smartphones, and many smartphones only support USB 2.0 speeds over their USB-C ports. Manufacturers assume that there is little benefit in wiring full USB 3.x capability when many common devices cannot take advantage of it. As a result, the adapters are optimized for the most common real-world usage, not for maximum possible performance.

In the end, manufacturers do not omit the extra pins because copper is expensive; they omit the pins because SuperSpeed wiring demands precision, USB-C compliance is strict, high-speed failure rates are costly, USB 2.0-only units are cheap and dependable, and most consumers never notice the difference. The same logic explains why some USB 3.0 flash drives internally operate only at USB 2.0 speeds—the cost of maintaining quality control for high-speed performance exceeds the price of the additional copper.