Why DoD Erase Doesn’t Work on Flash Memory (and What Actually Does)

Why Multi-Pass DoD Erase Schemes Don’t Translate to Flash Memory, Despite Being Widely Referenced

For a long time, secure erase meant one thing: overwrite the data. Then overwrite it again. And maybe again, just to be safe. That approach worked, it was measurable, and it aligned neatly with Department of Defense guidance written in the late 1990s.

This used to be true. It isn’t anymore. Let’s all stop pretending otherwise.

The problem isn’t that DoD erase guidance was wrong. The problem is that storage media changed — fundamentally — while many erasure habits did not.

Why DoD erase existed in the first place

Classic DoD overwrite schemes were designed for magnetic media: hard drives and tapes where data lived in fixed physical locations. Every sector was directly addressable by software. If you wrote new patterns over an old sector enough times, you could reasonably assume the original magnetic domains were gone or unrecoverable.

Multi-pass overwriting wasn’t superstition. It addressed real forensic techniques aimed at detecting residual magnetic patterns. The assumptions made sense because the hardware cooperated.

Flash memory does not.

Flash memory breaks the overwrite model

NAND flash storage — USB drives, SD cards, microSD, CompactFlash, SSDs — introduced an abstraction layer that magnetic media never had. Data is no longer written directly to fixed physical locations. Instead, a controller manages where data actually lives.

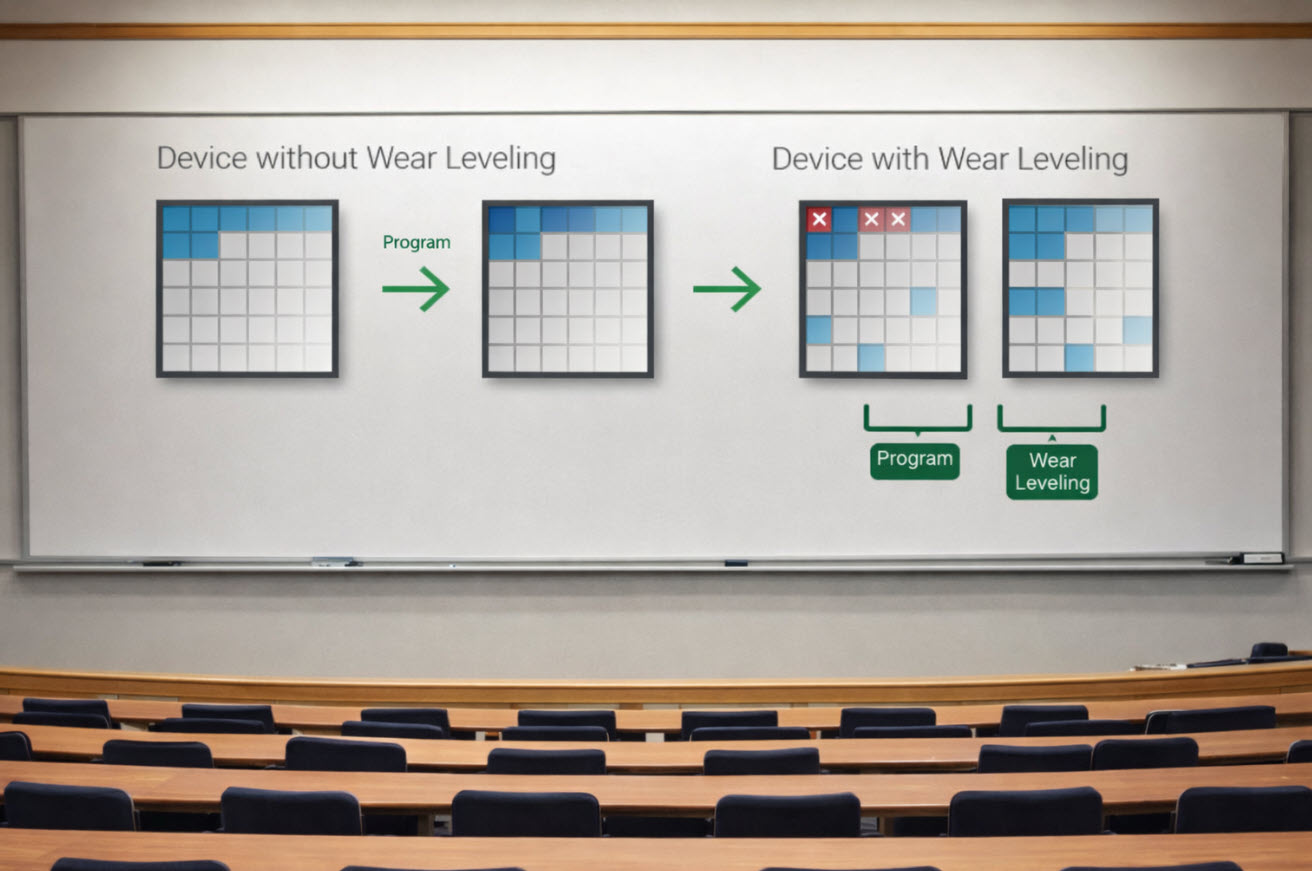

That controller performs wear leveling, block remapping, and bad-block retirement. Logical block addresses presented to the host are mapped dynamically to physical NAND cells. Some physical blocks are intentionally hidden. Others are retired after errors. Many are never directly accessible through the standard read/write interface.

Which means a simple but uncomfortable truth: software cannot reliably address every physical block on a flash device.

This isn’t opinion. It’s now explicitly documented in modern sanitization guidance. Overwrite-based erasure cannot guarantee removal of all previously written data on flash media because not all memory locations are reachable by the host.

Why multi-pass overwrite doesn’t save you

At this point, some people reach for the old instinct: “Fine, then overwrite it more times.”

That logic made sense when overwrite coverage was deterministic. On flash, it isn’t.

Multiple overwrite passes do not increase certainty. They often do the opposite. Repeated writes trigger additional wear leveling, increasing the chance that data is moved into spare or remapped blocks — exactly the areas the host cannot see or touch.

Flash memory also doesn’t retain analog residue the way magnetic media does. There are no fading magnetic domains to worry about. If you could overwrite every cell once, that would be sufficient. The problem is not how many passes you write. The problem is that you don’t control where they land.

More passes don’t mean more coverage. They mostly mean more optimism.

So can flash memory ever be fully erased?

The honest answer depends on what level of assurance you require.

Host-based overwrite alone is not sufficient for high-assurance sanitization. It can clear logical address space, but it cannot prove that all physical NAND cells are cleared.

Controller-level secure erase or sanitize commands can be effective — if implemented correctly. These rely on firmware instructing the controller to invalidate mappings, erase internal blocks, or abandon retired regions. They work only to the extent that the controller firmware is trustworthy and properly designed.

Cryptographic erase, where all data is stored encrypted and the encryption key is destroyed, is currently the most practical non-destructive approach for invalidating all data — including hidden blocks. But again, this depends on correct implementation and key handling inside the controller.

Physical destruction remains the only method that is provable without relying on firmware behavior. That’s why it still appears in the highest-assurance policies, even when it’s operationally inconvenient.

The practical reality organizations live with

In real environments, most organizations are not operating at intelligence-agency threat models. They need devices cleared for reuse, redeployment, or controlled disposal. They need consistency, documentation, and reduced risk — even if absolute physical eradication isn’t achievable.

This is where disciplined erase processes still matter. Using controller-aware tools to perform validated logical erasure, combined with clear policy boundaries about when cryptographic erase or destruction is required, is far better than blindly applying outdated assumptions.

It also means being honest about what an erase operation actually accomplishes — and what it does not.

Why this matters more than ever

Flash storage is everywhere. USB drives, SD cards, microSD, CompactFlash — the form factor changes, but the underlying behavior does not. Treating all storage media as if it were still a 1998 hard drive quietly increases risk.

The takeaway isn’t that flash is unsafe. It’s that sanitization methods must match the media. When they don’t, the gap between perceived security and actual security grows.

Tools and platforms like Nexcopy exist to bring structure and repeatability to that reality across flash-based media types. They don’t change the physics of NAND. They help organizations apply the best available controls — consistently, visibly, and with fewer assumptions.

Secure erase didn’t stop working. Storage changed. The sooner we acknowledge that, the better our policies — and outcomes — will be.

How this article was created

This article was drafted with AI assistance for outlining and phrasing, then reviewed, edited, and finalized by a human author to improve clarity, accuracy, and real-world relevance.

Image disclosure

The image at the top of this article was generated using artificial intelligence for illustrative purposes. It is not a photograph of real environments.

Tags: data destruction standards, DoD erase, flash memory sanitization, NAND wear leveling, secure erase methods